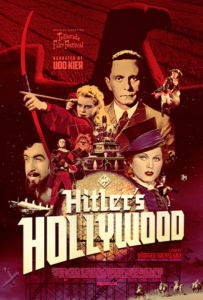

Take a wild guess what Ingrid Bergman did between leaving Sweden and coming to Hollywood. No, she didn’t go to Italy and make a porno flick (that I know of), but she did stop in Germany long enough to appear in a Nazi propaganda film about modern women. That’s the most striking revelation in Rudiger Suchsland’s fine 2017 documentary, “Hitler’s Hollywood” (available on DVD from Kino Lorber), but certainly not the only one. The film is a constant surprise, since most of the more than 1,000 pictures made in Germany between 1933 and 1945 are unknown and have been virtually unseen since the war.

It wasn’t lost on propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, who oversaw the Nazi film industry, that cinema was above all a distraction and created the illusion that things weren’t so bad during the Third Reich. Half the movies were musicals and comedies; among others they made their own version of “It Happened One Night,” a Sherlock Holmes film, and an allegorical picture about the Titanic that was banned in Germany. No horror films, however, which were judged “too close to reality.”

As might be expected there are scenes from Leni Reifenstahl’s notorious “Triumph of the Will,” elevating Hitler to the status of a preacher or a deity. We see clips of actors like Brigitte Helm (the femme fatale of “Metropolis”) and films by such directors as Douglas Sirk. There are samples of Oscar-winning silent star Emil Jannings’ Nazi era work but no discussion—a glaring omission, given his fame. Udo Kier’s narration is difficult to hear at times but no subtitles are offered.

Some filmmakers find humor in the most unexpected places, even amongst the refugees in the ravages of Germany during the postwar era. That’s the conceit of Sam Garbarski’s entertaining new dramedy “Bye Bye Germany” (in German with English subtitles, available on DVD from Film Movement), whose protagonist David Bermann (played by Moritz Bleibtreu) tells us the story of how he received special privileges in a concentration camp by acting as a “court jester.”

Adapted by Michel Bergmann from two of his novels and apparently based on a true story, it’s a disarming tale. Our hero charms not only the U.S. Army interrogator (Antje Traue) to whom he reveals his past, but the many customers to whom he and his friends sell linens, to raise funds to help them emigrate to America and Palestine. A bonus animated short, Erin Morris’ brief but impressive “Strings,” was inspired by the work of a violin maker who restores violins that survived the Holocaust.

What “Go, Johnny, Go!” (available on DVD from The Sprocket Vault) lacks in plot or drama this 1959 rock ‘n’ roll musical makes up for with its cast. Ostensibly, it’s about a disc jockey’s (Alan Freed, who played himself and also produced) search for the next big star. This threadbare premise is really just a sublime excuse to showcase the talents of rock pioneer Chuck Berry, the tragic Ritchie Valens (in what’s billed his “farewell appearance”), Jackie Wilson, Eddie Cochran and Jimmy Clanton (who’s still performing at 80) and others.

My old friend Randy Skretvedt, one of a trio of film and music historians who provides commentary on “Johnny,” has just compiled and annotated “The Laurel & Hardy Movie Scripts” (available in paperback from Bonaventure Press). This compendium of 20 screenplays for the team’s 1926-1934 comedy shorts offers a treasure trove of material written with the duo in mind but never used, because they preferred to improvise as they were filming. Skretvedt offers fascinating details on the differences between the films and their scripts, including several for L&H’s silent shorts which I was happy to provide.

Recent Comments